Album covers

Live shots

Film shots

click on images to view Bowie collages

The David Bowie Question: On Making Decisions

By Wilder Penfield III

It is the thirtieth anniversary of my meeting rockstar David Bowie, my first important professional interview, and ragtime legend Eubie Blake. I'm thinking once again about the infinite richness of possibility, and about the widely different awarenesses of choice each of us brought to our encounters.

Evolution hasn't had time to adapt us to the modern world. Most of the history of our species was spent on African savannas, where the decisions we had to make were rather primitive. (Question: What should I be when I grow up? Answer: A hunter-gatherer.)

And even when our prospects finally became a bit more complex a few millennia back, most of humankind were still being defined by the circles into which they were born. (Answer: Whatever your dad does. Or mom, if you're a girl.)

The modern world isn't very old. Eubie Blake could recall when there was either live music, or the mechanical piano, or no music at all. He was 96, still demonstrating his gift in performance on real pianos, still smoking unfiltered Pall Malls one after another. I asked him what he would do first if he could be dictator for a day. He thought, but only for a moment: He would legalize abortions. "I think every human being should own his own body."

His parents had not owned their bodies. They had been slaves. Eubie was the first baby to survive of 11 his mother had had. His father, though, was used as a stud and knew for sure of 27 children with his genes.

"Freedom of choice" became globally pervasive as a concept only within living memory, when all the world began to mirror its variety on screens that may already outnumber people.

So what protects us from the shock of choice-overload?

I have become convinced that it is the combination of absorption and abstraction that Armenian mystic G.I. Gurdjieff called "sleep" and that Toronto psychotherapist Adam Crabtree called "trance ... the spell of conformity."

When I fell in love, I was entranced, and the field of my potential partners plummeted from countless to one. Being reborn in Christ seems to result in equivalent euphoria and in similarly radical simplification. So does devotion to an innate gift - which must have served to preserve the delight-fullness of Eubie Blake.

If we haven't broken the enchantment of family or the pressure of peers, many of our decisions are happening subconsciously. I found that trying to fit in can corral a lot of upsettingly free time.

Today, cultural trance is characterized by the nexus of money and power and fame, making it seem important to keep up with "who's who" and "what's hot". It redirects our attentions and reframes our concerns so that we focus on the shifts in body-image and fashion, the rankings of guiltiness and greatness, the chances for peace, the war on terror. As award-winning novelist Thomas Pynchon wrote, "If they can get you asking the wrong questions, they don't have to worry about answers."

I have always been a writer because writing was what I did when I was off-leash. I became a journalist to support my habit, and that wasn't really a decision, either. I had only to say yes when opportunity knocked.

But things had begun to change when I met David Bowie - I had made that opportunity happen.

I didn't know what to expect of him - he was forever reinventing himself - but I sure knew what was expected of me. I had a music column or feature seven days a week in the Toronto Sun. "Light, bright and tight" was the Entertainment style. "Mass rather than class" was the preferred content. And while columnists had remarkable freedom within those parameters, "free" was the ideal budget. (It was bad to be bought, of course, but fine to be facilitated.) So it was with considerable difficulty that I had persuaded his record company to persuade Bowie to include one Canadian in his one day of American promotion for his album Lodger. And it was with considerably more difficulty that I had persuaded the deciders at the tabloid to set a precedent and fly me to New York for the occasion.

In those days, The Little Paper That Grew was proudly local ... except when it was humbly limbic. The caricature was bodies on page one, female bodies (provocatively garbed) on page three. The frequent flyers on staff were either following our sports teams or pursuing crime, disaster, scandal, or real (Hollywood) stars. Bowie wasn't coming to town, he didn't have a current hit, and he was weird. He did have major sex appeal, which forgave a lot. But could I get something different from what our wire services would serve us? The deciders had their doubts. And yet ...

Not long before, overwhelmed by whim, I had interrupted my account of a Barry Manilow concert - mid-paragraph - with "(This is getting boring. I'm going to give away a pair of Bob Dylan tickets to the first person who phones me at [my Sun number] after noon today with the correct answer to the following question: What number preceded by 2 is double the same number followed by 2? Now back to the review.)" The question is simple, but the lowest answer turns out to be in the tens of quadrillions, and I assumed my promotional tickets would be going to the friend who had given me the question.

When I came in the next morning, though, the switchboard operators were outraged. With a new phone system only partially installed, any phone numbers greater than mine were receiving calls no one knew how to respond to.

By noon, every such number in the building was being staffed by people I had profusely apologized to and had supplied with the 17-digit solution, and although more than a few of the calls were along the lines of "Is it seven? Aw, cmon lemme guess again!" well over a hundred callers were correct in the first quarter-hour. (My friend said he tried speed-dialing me for 30 minutes before he gave up.) Repercussions included executive tongue-lashings, promotion department admonishments ... and editorial recognition that there might be an audience below the radar of our marketing surveys.

A few nights later, the news desk was actually considering front-paging a wonderful photo from a downtown autograph session of scraggly Mother of Invention Frank Zappa signing a trim expectant mother's bare bulge, and they asked how I thought "my people" would react. (Shock, I guessed, but I predicted they would mock any establishment outrage.) The picture ran, the outrage made TV news, and the countervailing scorn of "my people" came in bales.

A few weeks later, we helped promote the giant talent of lyricist and singer Demis Roussos by getting his luxury hotel to make him the world's largest hamburger and front-paging his first bite. Another whim, another win.

So there had been some receptivity when I told the deciders I could have a lot more fun with David Bowie than news agencies would. Let the wires tell everybody about the star stuff (success, money, fame); what we wanted for a big dramatic dishy splashy crowd-pleasing spread was a lively exchange about, uh, personal things, things he had in common with the man on the street.

The suits didn't think I had much of a clue about the man on the street, but the entertainment editor had gone to bat for me, and so okay, I was going to have a chance to knock their socks off. One chance. Good luck.

Why put my fledgling career on the line for Bowie? I wasn't a fan. Intrigued, yes, but not impassioned.

And that was fine. I had deliberately set aside my personal tastes and made it my business to appreciate all kinds of music from a cappella to zydeco, and sooner or later there were performers I was passionate about in just about every genre. But what I personally enjoyed reading, and trusted, was enthusiasm or fascination, not contempt, no matter how clever. My form of the good had become a review so vivid and evocative that a satisfied punk and a horrified parent would both assume I agreed with them.

David Bowie went on to become a really big deal - his career moves became business news, for heaven's sake - and rock (especially 70s rock, oddly enough) has evolved into the default soundtrack of our culture from arena sports to TV spots, so it may be hard to remember that these conclusions were far from foregone in 1979. The corner officers were not wrong to be doubtful. What I knew was that Bowie was a man of many cults, that he was consistently "good copy", and that he embodied both sides of some very divisive issues. Could I get him to address those issues?

The exchange itself was not a concern. Almost no one (dumbfoundingly!) is threatened by the prospect of conversing spontaneously. Unless paralyzed by feelings of inferiority, we are likely to take it for granted that our choice of suitable sentences will arrive from some unboundaried limbo to represent ideas that somehow will be generated in us at the moment we require them.

Compare that easy hubris, though, with the inner knots that are tied by most people, even pros such as Bowie, when they are faced with the prospect of performing - even when every word, note, or move can be planned and practiced in advance, even when responsibility can be shared with a superlative team, even when the audience is dominated by friends or fans who would forgive you anything. (Such knots also emerge in many people who write on demand, even though they can edit themselves as they go, present company not excepted.)

Here Bowie would not be facing the challenge of the blank page or screen or performing polished artifice for a few friendly thousands - he was simply going to talk about what mattered to him ... with a total stranger of unknown motives ... who would record this private improvised dialogue and use any excerpts in any context the stranger chose.

Bowie would have to expect that any one impulsive remark could be international news tomorrow, recycled forever - like the moment when John Lennon was struck by the irony that the Beatles seemed more popular than Jesus. Not much he could do about that once the moment was over. Not much any of us could do, but most of us would not have to do anything. Most of us are not trapped in the amber of celebrity.

But if Bowie was not going to be nervous, even after weathering years of controversy (only some of it deliberate), he would surely be guarded, instinctually if not consciously. Could he be disarmed?

On the combined evidence of hundreds of profiles, he was an intuitive chameleon who (actively? passively?) took on the colors of what was desired. Interviewers who came to sit at the feet of the master were given evidence of mastery. Those who came to cut him down to size were satisfied that he fell short. He ministered to those who wished to be converted, amused those who sought entertainment, dueled with the pugnacious, chummed with those who needed a friend.

Getting what I wanted from Bowie would apparently depend on who I was, or who I seemed to be.

And it came to me: All I needed to be was someone who genuinely liked him.

And that was easy - I had recently determined that I could like almost anybody I could know enough about to understand. Over and over again, I had found that intent was defining - under normal circumstances, one sees what one chooses to see. I had chosen to find connection with what newagers were calling the light in people, and to trust that connection not as the whole story but as the source of an important story. Unlike almost anyone else in the always skeptical and often cynical heart of journalism, I had found a way to make what I would come to call a choice for happiness.

But the process was not yet complete, and maybe it never will be. Certainly when career moves don't go according to plan, I still feel threatened. And I felt threatened when I checked into Bowie's hotel and showed up at the appointed time at Bowie's suite and found not Bowie but a score of journalists with appointments scheduled ahead of mine. Bowie was sorry, we were told, but he had been delayed in L.A., and he was stopping off en route to Europe, and he regretted that he would have time to answer only one question from each of us. In private.

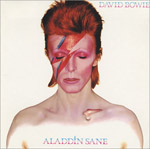

After casting about unsuccessfully for collaborators, I started to sweat. One question! How about one for Ziggy Stardust, one for Aladdin Sane, one for the Thin White Duke of "Plastic Soul" and one for the Man Who Fell To Earth? I was ready to ask him about things he had said in countless previous interviews, about every song he had recorded, about every role he had played on stage or screen. Should I ask about his art? His lyrics? His business innovations? His Heroes? His strange choices of collaborators, friends, lovers? (The Sun would be thrilled if he would only admit to a relationship with Mick Jagger.) What about his relationship to drugs and other escapes? What about the future, the one that "belongs to those who can hear it coming?" How could I choose? Heck, how could he choose?

Ding!

How did he ever find himself choosing with any kind of commitment?

It's amazing enough that any of us makes the decision to do anything. It's even more amazing that most of us feel reasonably good about the decisions we have made, most of the time, when you consider the limitless number of things that any of us could have done. No wonder we rely so much on momentum, and submit so readily to accidents of circumstance. No wonder so many of us find comfort in letting habit or addiction choose for us, and no wonder the path of least resistance so often seems to be some kind of circle, even if eventually, with luck, it turns out to be a spiral.

Bowie must be getting ideas all the time, I assumed, and amazing offers, and seductive distractions. He hadn't made choosing any easier for himself - he hadn't defined exactly what he did for a living, or who he wanted to be when he grew up and stopped ch-ch-ch-changing. And yet he obviously functioned effectively. He did decide, over and over. Surely if someone as battered as he by the knocking of opportunity could make satisfying choices, so could any of us.

Which is how I prefaced the question when I was finally ushered into his presence. I accompanied it with a request for specifics where possible; abstracts wouldn't win much space at my paper. Bowie seemed delighted by the challenge, eager to explore his surprisingly various processes, and willing to range widely for detailed examples.

The first task was to be fully present, he said, speaking softly. Yes, in the Buddhist sense.

"I'm working in inner space at the moment, and I'm finding a quite extraordinarily large universe in my own character that I had long neglected. I'd been filling my head with too many other characters and people for a long time." [I will call this, as neutrally as possible, a choice to pluralize.]

The characters weren't him?

"Oh Lord no!"

Parts of him?

"Well, with a writer, of course, the characters are all about oneself and nothing about oneself. It's hard to associate which bits fit in or come from where. I'm a ravenous eclectic, totally open and vulnerable to atmosphere and environment, so everything that passes my eyes goes in, and comes out at a later stage. So even for me there are aspects of my writing that I really have no idea about what they may mean ..."

David Bowie was born David Jones in South London, on Jan. 8, 1947. A high school dropout at 16, he worked as a commercial artist and played sax for local bands before forming David Jones & The Lower Third, which recorded one album (buried then, treasured now). He changed his surname because Davy Jones, lead singer of the Monkees, was better known. His first album as David Bowie was in l967. Two years later, he had his first international hit with Space Oddity, which he recorded after seeing 2001: A Space Odyssey. Other influences over the next decade included Bob Dylan, Anthony Newley, jazz, mime, Buddhism ...

"I know about the input," he was saying; "the output is something else entirely. More and more now, there's far more information on an album than I put in. I can listen to it and feel that I am listening to somebody quite dissociated from me.

"My premise for making Low and Heroes and Lodger was to experiment with new methods of writing and to evolve some new musical language for myself - I had been floating with fragmented-thought techniques since Diamond Dogs. Now I wanted to go whole-heartedly into that area and see if I could derive some more motivation to continue writing - otherwise I would have stopped."

Part of his motivation was to serve at the front. "I mean, God, rock always wanders in about 10 years after all the other art forms, and I am intoxicated with the idea of applying other methods from other art forms immediately to rock and roll to make it a contemporary situation." He singled out the importance of William "Naked Lunch'" Burroughs to his thinking, also composers-performers Philip Glass and Steve Reich, and mentioned Soft Machine as a rare exception to the lack of innovation in rock. "I wish to feel that the music I am producing does illustrate very much of the particular year and the particular place I was in ..."

The particular place??

"I don't work well in a comfortable situation. I never have done."

I found it ironic that we were talking in his room at the Mayfair, which he thought of as "his" hotel, the one he always chose when he was not staying with New York friends. It was the kind of place you'd want to run barefoot through, carpeted knee-deep, inward looking, peaceful, with uniformed servants discreetly operating elevators, hailing cabs for you, bringing newspapers and messages on glove-handled trays. But for him, it was a lair, and he moved in it smoothly, gracefully, constantly, like a mutant panther. He wasn't talking about foregoing creature comforts.

"I have to not understand a city too well to be able to work in it. I'd had quite enough of Los Angeles and all its silly bizarreness, and it was affecting me adversely, no doubt about that; I'd gotten caught up in some of the nastier points of the place. So I thought it time to make a move, and I looked for the next city that would provide me with the friction necessary to write; West Berlin sounded ideal. [A choice of the Shadow Warrior.]

"The studio we found was only a few metres away from the Wall, and we could see a turret on top where the East German guards had their sub-machine guns; we worked with that visual all the way through ..."

Next,"I think we might make a rapid move to some other location, some situation where I can remain anonymous and be an observer. I think it's pointing towards Japan. There's always an indication of what and where I'm going to be next, though I often don't recognize it until afterwards ..."

Lacking true predictive powers, he had chosen to look for guidance in anomalies [a choice to cultivate intuition]. So, for example, when he found himself oddly obsessed with the desire to add Japanese sounds (koto, bells) to the later tracks on the Berlin trilogy, he took it as a sign ... and would be primed for a return to acting when he was offered the role of a Japanese prisoner of war in Nagisa Oshima's Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence (1983).

Besides, he was attracted to anomalies regardless. Hence his decision to make a rare prime-time network appearance on Bing Crosby's Merrie Olde Christmas. They asked him. "I don't think they knew too much about me," he said with enormous delight. "I think they probably knew Fame and a couple of other things, and they probably saw me on the Dinah Shore show and realized I didn't spit much on the floor, so they thought I was probably fairly safe.

"When they approached me, they were quite upfront about it, they needed somebody from (cavernously) The Contemporary Situation.

"I thought it would be an incredible experience, so I said of course I'll do it, I'd love to do it [a choice to go with the flow]. Now that he's gone, I feel particularly lucky to have had this chance. I did a piece of music from my area, and I did a duet with Bing Crosby, which I am so proud of - we did Little Drummer Boy."

"Did you do the pa-rum-pum-pum-pums]?" I asked.

Bowie was scandalized: "How could you take that away from Bing?" he protested. "He was pa-rum-pumming all over the place with astounding resonance - it was terrific stuff."

Before that, well, there were a lot of changes between The Man Who Sold The World with a 1970 album and The Man Who Fell To Earth in a 1976 movie.

The next project he accepted was the role of Austrian Expressionist painter Egon Schiele in a Clive Donner movie to be called Wally.

"I'll tell you why I wanted to do it. I was a painter before I was a musician, and I was an Expressionist painter at that - I think that's still fairly obvious in the way I approach music. But I considered myself somewhat of a failure as a painter, and so the chance to play a successful Expressionist painter appealed to me tremendously. And the script was excellent. And there wasn't one alien in sight.

"And while it was a quiet film, I thought It would be quite sensational because the subject matter was seemingly so conservative. I mean, he was an alarming man. A little instance - when he was dissatisfied with the way his painting was going, he would take his painting into a field and beat it with a stick, to teach it a lesson, to discipline it, and then bring it back into the house and continue painting.

"I've always wanted to do that, beat a painting. I have small ambitions."

He recalled that at 12 he was attracted to what was commercial - art? Sure, why not! - because he believed that if he could imagine his success, he could will it and escape from the damage of what he considered to have been family "madness."

The eyes have it. One blue, one grey, with one pupil much larger than the other. Some people discovered this for the first time in The Man Who Fell To Earth, but check the album jackets - this wasn't an optical trick, it was an optic near-disaster, a childhood fight with friend George Underwood (who would one day design several Bowie albums). Surgery saved his right eye, but paralyzed his left pupil.

Often he seemed to be looking simultaneously at you and beyond.

"I had to be very exaggerated at the beginning," he told me. "But I'm pretty satisfied with my own individuality now. I've given up adding to myself, stopped trying to adapt. No more characters."

Well, maybe just the role of "Bowie"?

"Artistically, of course, I'm in constant flux," he admitted. "But as a person, I'm becoming a lot more rational and emotionally composed as I get older, and I welcome the age I'm moving into with open arms."

The age he was moving into was 33. Berlin had cleared him of the drugs that made it difficult for him to separate himself from his characters. "I'm glad I did everything I did ..." But he knew too much about the dangers to recommend his son follow his footsteps (and too much about psychology to try to prevent it).

He did not seek to be a hero to his son. He had never sought to be a hero to his culture. "My characters were the heroes." If fans continued to follow his every transformation, well, "I'm quite amazed, and I applaud them highly. (Laughs.) I mean, I have enough trouble keeping up with myself!"

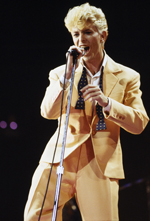

If he was going to repeat something, it would be the bright neon white he had used on tour. "Quite honestly, I found that a wonderful environment to work in, so straight-ahead that there was absolutely nothing to hide behind. Once you got all that office lighting on, I could see the 20th row - I could see the spots on the face of the guy in the 20th row, and I daresay he could see mine as well - it's that revealing ..."

Self-exposure, though, was also making him nervous. "Scared stiff, actually." Owning up to bisexuality "had a disastrous effect on my credibility as a composer and writer for a long, long time."

On the other hand, "It's hard to remain artistically illegitimate." And he couldn't let performance become secure. "I've got to have the element that surprises me, else I'm not on a panic-button level, which I've got to be to make the performance live."

He was also strongly attracted to not performing. Several times, he had promised himself that the 1976 tour would be his last. Movies were being contemplated with Fassbinder, Wertmuller, Bergman. Even more, he was being drawn back to his art. Maybe all this Expressionist music would prove to have been a long detour. And maybe not. "As long as I create out of the enthusiasm of a particular moment, I cannot envision any period of creative stability ..."

One of the things the Sun excels at is excess. The day after Elvis Presley died (two years previously), we devoted 30 pages to him - overkill, but memorable. The editors responded to The Many Faces of David Bowie (I used almost every word he uttered) with a syndicated series of four features. And I was able to follow up with a series on the Grateful Dead at home. Soon, I was traveling far and wide to preview incoming rock tours, and following Rush and Triumph and other local bar bands to arena breakouts in the United States, making upward of 40 out-of-province trips a year. (Be careful what you wish for ...)

By then, the David Bowie question, the Decision question, was at the heart of every interview I did. Almost always it at least tuned people usefully to my wavelength, suggesting that I wanted to talk about things that mattered to them. Never, amazingly enough, did it shut down the conversation.

Nobody said that they had no idea, which would have seemed a perfectly reasonable response, or that it was none of my (readers') business, which would also have seemed fair. Sometimes it might take two or three tries to find a congenial approach: What is the best thing you have done with disposable income or fame or free time? What makes an inspiration feel like your kind of inspiration?

Although never again would the David Bowie Question generate a response quite as forthcoming and wide-ranging and delighted as it did from David Bowie, always it elicited feelings and ideas about values, and my process of probing individual celebrity for common-denominator humanity had begun.